11 Sep CÉLINE

Bookcase

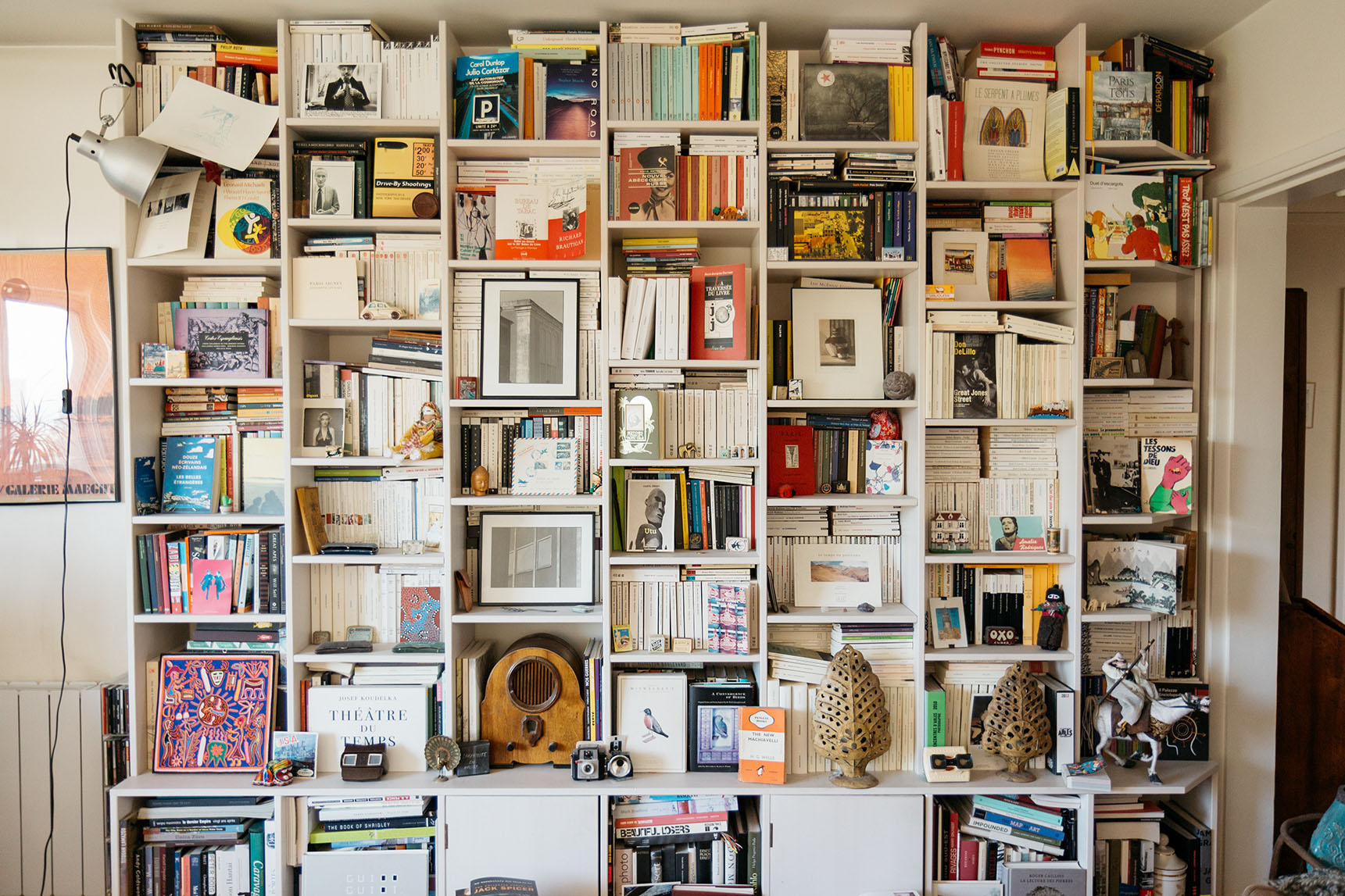

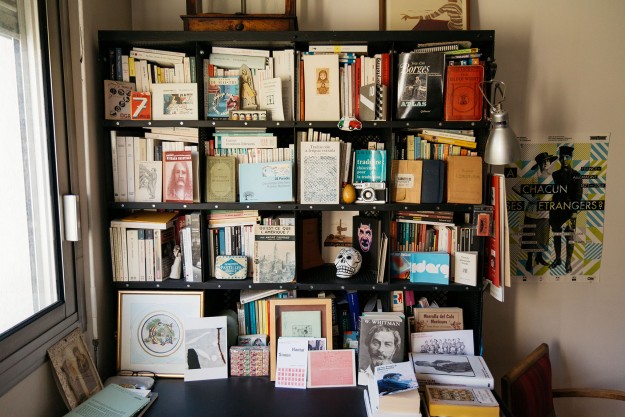

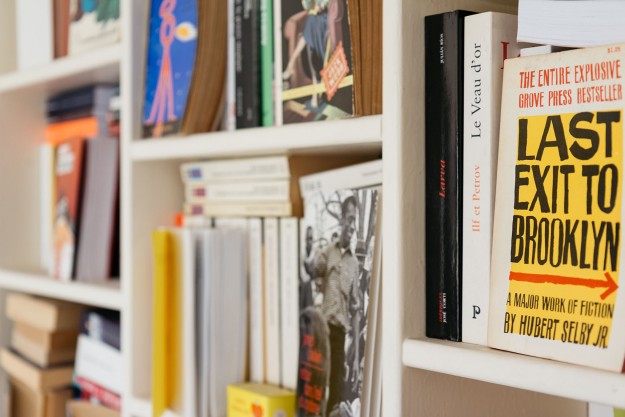

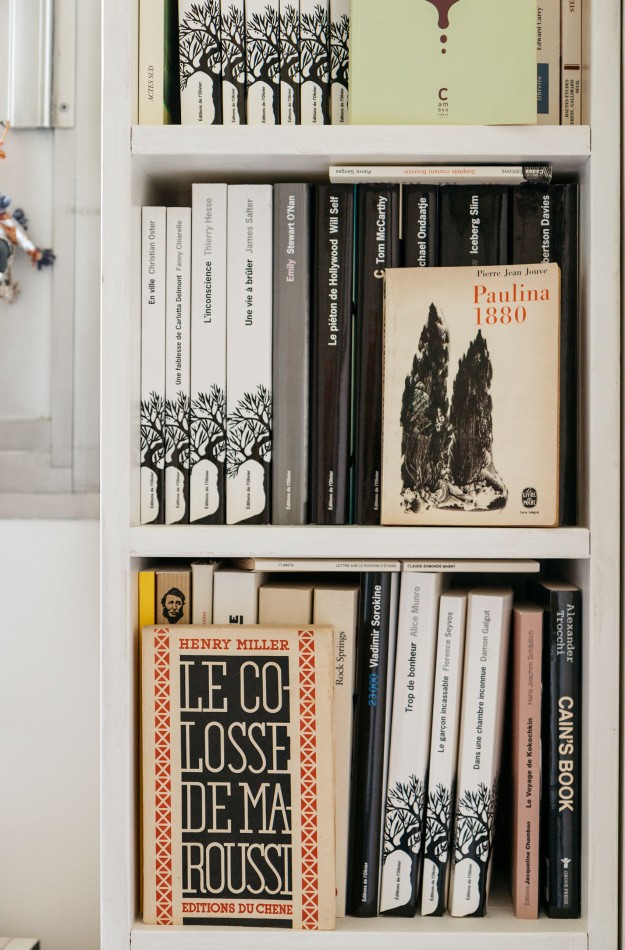

Céline has been living in this flat of the 20th arrondissement of Paris for 11 years, but she has always known it: it belonged to her grandparents. “It is also the place where I work” adds Céline, a translator from English to French. No need to look for the bookcase: there are books everywhere. In her office, in her bedroom and in the living room; on the shelves that have been made by her father, but also out of the shelves. The books are part of the apartment’s decoration. “There is a classification by publishing houses except when I am overwhelmed, which is the case right now!” she laughs. We see Silvia by Leonard Michaels. “An important author in my career as a translator. I am happy to have it in front of my eyes.”

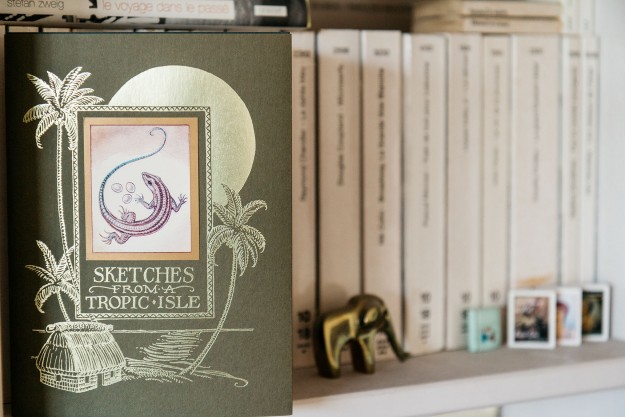

In front of the living room’s bookcase, Céline explains: “Here are the books that are linked to the past. I sometimes feels invaded but it remains an extremely lively bookcase.” Amongst the books are plenty of objects that come from her travels, gifts from family and friends, memories from childhood. Each one carries its own story. Exactly like books.

The novels she read remind her of periods of her life and the ones she hasn’t read yet are reassuring: “all these marvels I still have to discover!” And Céline to conclude: “a book is comforting, it is a great insulating material from the outside world.”

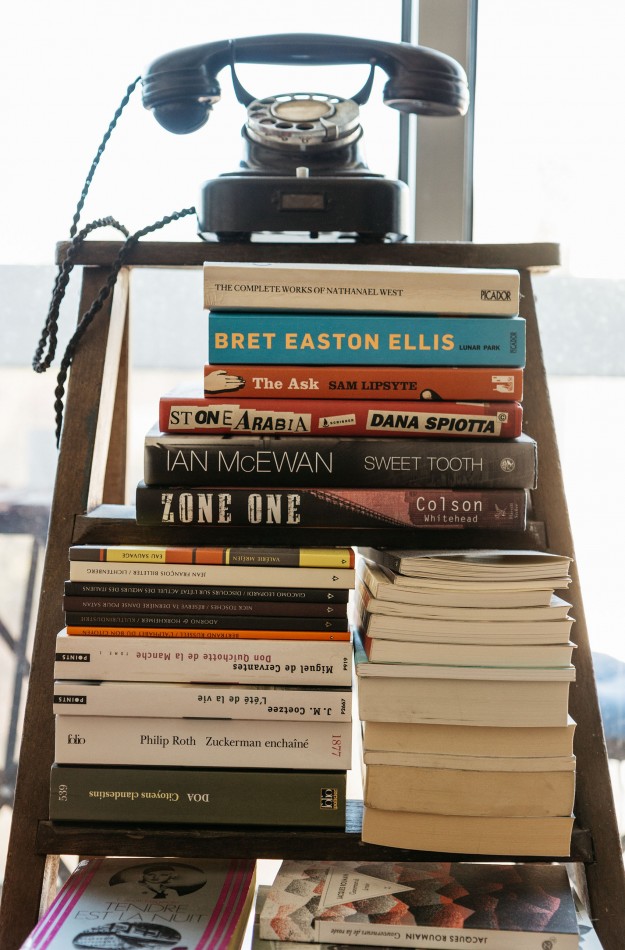

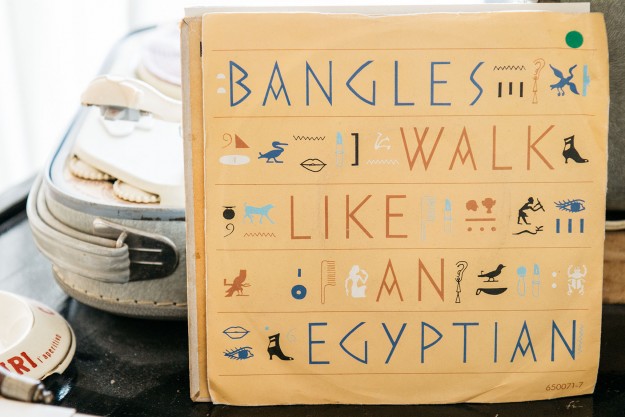

Readings

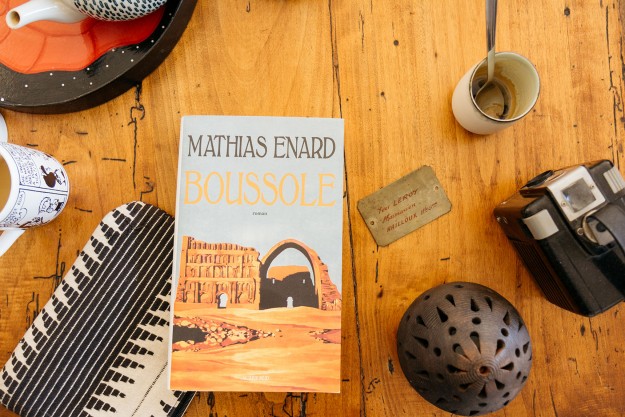

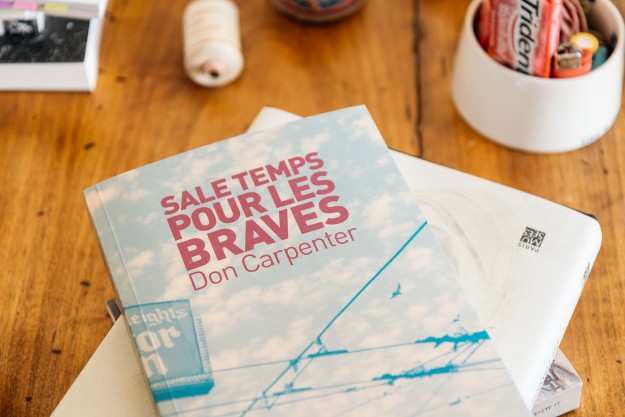

Through her studies and job, Céline has obviously read lot of literature by English-writing authors. She confesses a particular tenderness for Faulkner and McCarthy. And obviously for the authors she translates: Owen Marshall, Leonard Michaels, Don Carpenter, Jeanette Winterson, Renata Adler, Peter Heller to name a few. “Nowadays, when I read for myself, I favour French, Italian, South-American or German literatures.”

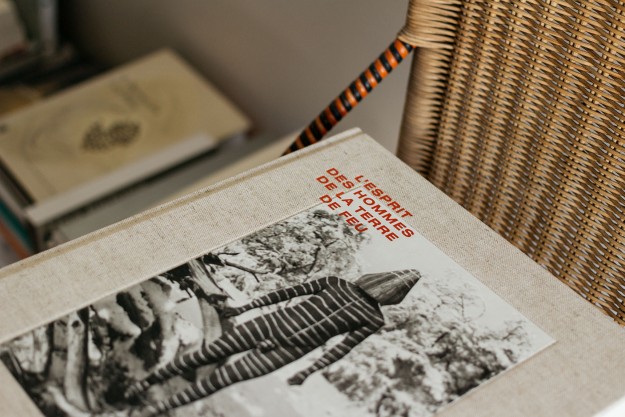

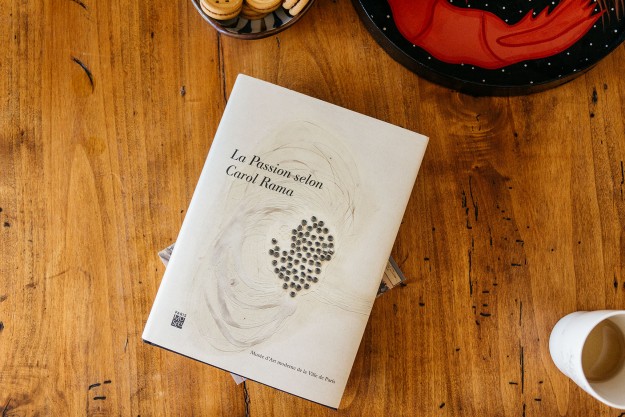

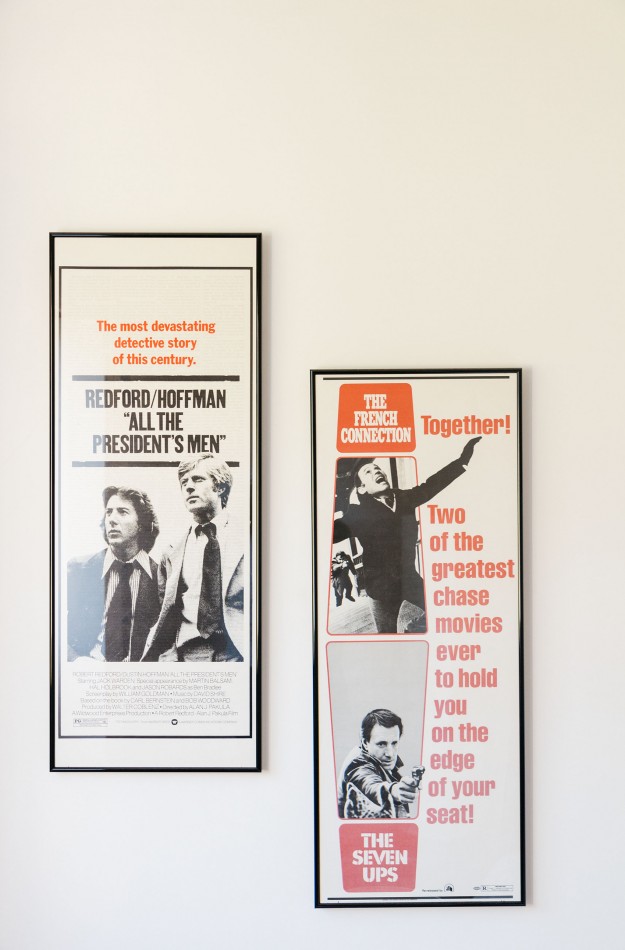

But it is not all about literature for Céline. “I have a compulsive relationship to pictures. I need to accumulate them. It is not enough for me to have them in mind.” Indeed, many art books and exhibition catalogues surround her.

Translation

Céline is a joyful and enthusiast person. Her luminous flat has a serenity feel. Not at all the sombre cave where the tormented translator would fight her demons that we imagined. “It is because I know myself well now: I deal with my discipline and my stress!” There is still a slightly complicated moment between two translations: “the anxiety of letting go the finished translation and the worry about discovering the difficulties of the new one.” Recently she cried when leaving the characters of a translation: “From the first page, I felt that I had known them for ever. The separation was painful!”

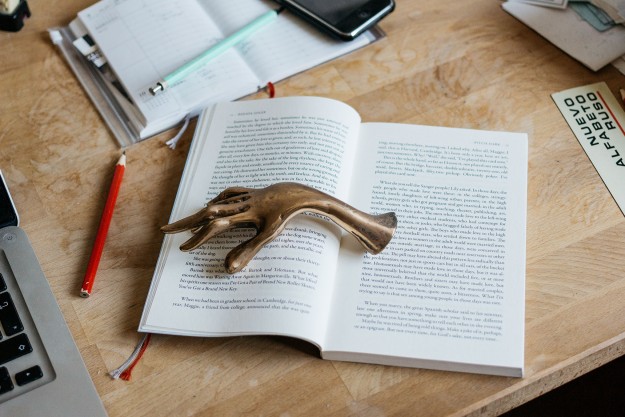

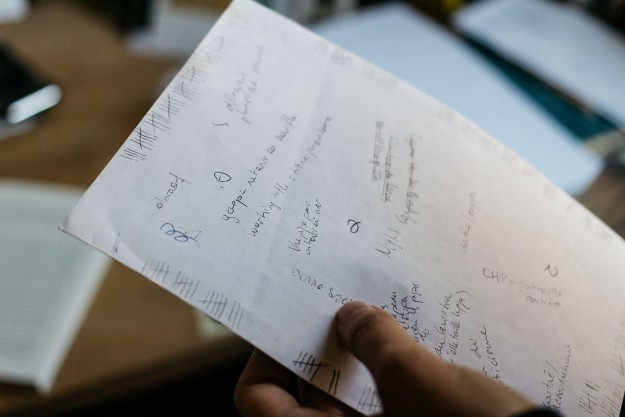

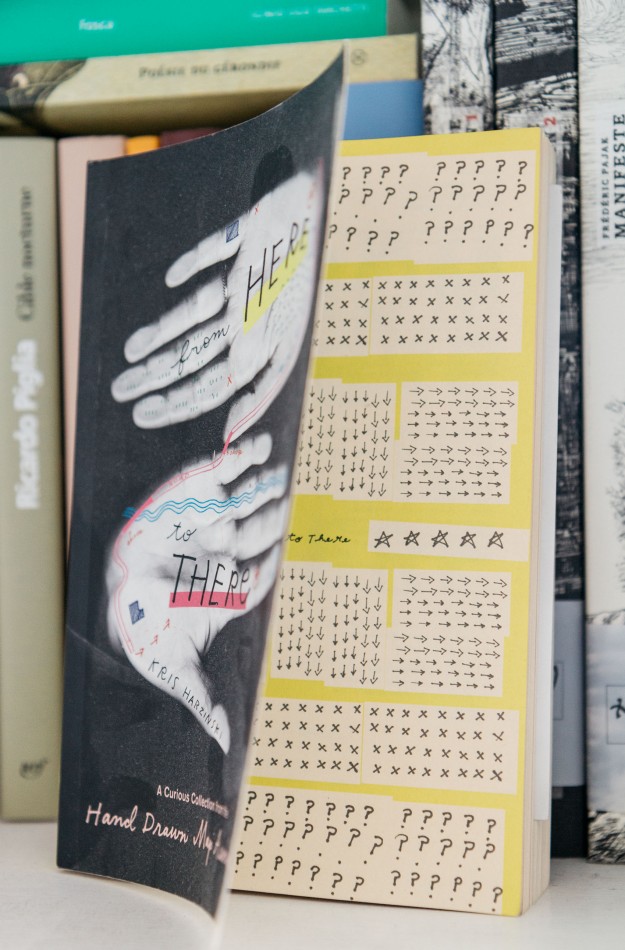

We observe her desk: there are numerous pictures – “entertaining and comforting” – a bronze hand – “a present from my godfather for my 18 year-old, I know use it to keep open the books I am translating” and some paper sheets covered with mysterious handwritings. “When I am translating, I write down the difficulties I meet to then come back to it. Then, when I am re-writing, I draw strokes to measure my progression… Like prisoners…” adds Céline, laughing. One of the authors she translates found one of these paper sheets one day: “He first thought I was crazy. But finally, I am still his translator!”

A FEW BOOKS TO BORROW FROM CÉLINE:

The Painter by Peter Heller, Vintage: After having shot a man in a Santa Fe bar, the famous artist Jim Stegner served his time and has since struggled to manage the dark impulses that sometimes overtake him. Now he lives a quiet life. . . until the day that he comes across a hunting guide beating a small horse, and a brutal act of new violence rips his quiet life right open. Pursued by men dead set on retribution, Jim is left with no choice but to return to New Mexico and the high-profile life he left behind, where he’ll reckon with past deeds and the dark shadows in his own heart.

A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor by John Berger et Jean Mohr, Vintage: Booker Prize-winning writer John Berger and the photographer Jean Mohr train their gaze on an English country doctor and find a universal man–one who has taken it upon himself to recognize his patient’s humanity when illness and the fear of death have made them unrecognizable to themselves. In the impoverished rural community in which he works, John Sassall tend the maimed, the dying, and the lonely. He is not only the dispenser of cures but the repository of memories. And as Berger and Mohr follow Sassall about his rounds, they produce a book whose careful detail broadens into a meditation on the value we assign a human life. First published thirty years ago, A Fortunate Man remains moving and deeply relevant–no other book has offered such a close and passionate investigation of the roles doctors play in their society.

The Men’s Club by Leonard Michaels, Farrar, Straus and Giroux: Seven men, friends and strangers, gather in a house in Berkeley. They intend to start a men’s club, the purpose of which isn’t immediately clear to any of them; but very quickly they discover a powerful and passionate desire to talk. First published in 1981, The Men’s Club is a scathing, pitying, absurdly dark and funny novel about manhood in the age of therapy.